I Don't Know... How Planes Stay In The Air

What makes us trust?

I was fortunate enough to be flying in a plane recently. It was New Year’s Day and, likely because of the drinks I’d had the night before, I was drifting in and out of an uncomfortable sleep.

I woke with a start with that sensation of not remembering immediately where I was. I looked out of the window and saw nothing but the clouds below.

As I woke up, I realised that I had no idea what keeps a plane in the air. A slightly fear-inducing thought when hungover at 36,000ft, but what was keeping this huge machine that I was sleeping on from falling back to Earth?

I realised that this thought had never even crossed my mind when boarding the plane, or on the dozens of other occasions when I’d gotten on a plane in the past. Somehow, I’d just generated trust that any plane I was about to get on would safely get me to where I was going.

What is it that makes us trust?

The definition of trust is a “firm belief in the reliability, truth, or ability of someone or something”. A helpful start, but I don’t think this gets to the root of why we generate that firm belief in the first place. Especially when it’s immediate for certain things and not others, or where certain people are quick to trust and others not so.

When considering the plane, initially I thought it was simply that the trust I had generated had been a result of how I had seen others behave. Because I first got on a plane with my parents and they had been relaxed and comfortable, was that enough to make me feel comfortable myself? But there are other examples, where I don’t trust in the same way as my loved ones. I have a mental block about sleeping tablets (I’ve never been able to take one), even though I’ve watched people close to me take them in the past with no issues.

Despite us largely having access to the same information, we don’t all trust equally and we don’t trust the same things. At the time of writing, according to a YouGov poll 69% of people deem Boris Johnson to be “untrustworthy”. What about the other 31%? What is it about ‘trust’, or the situation that is different for them?

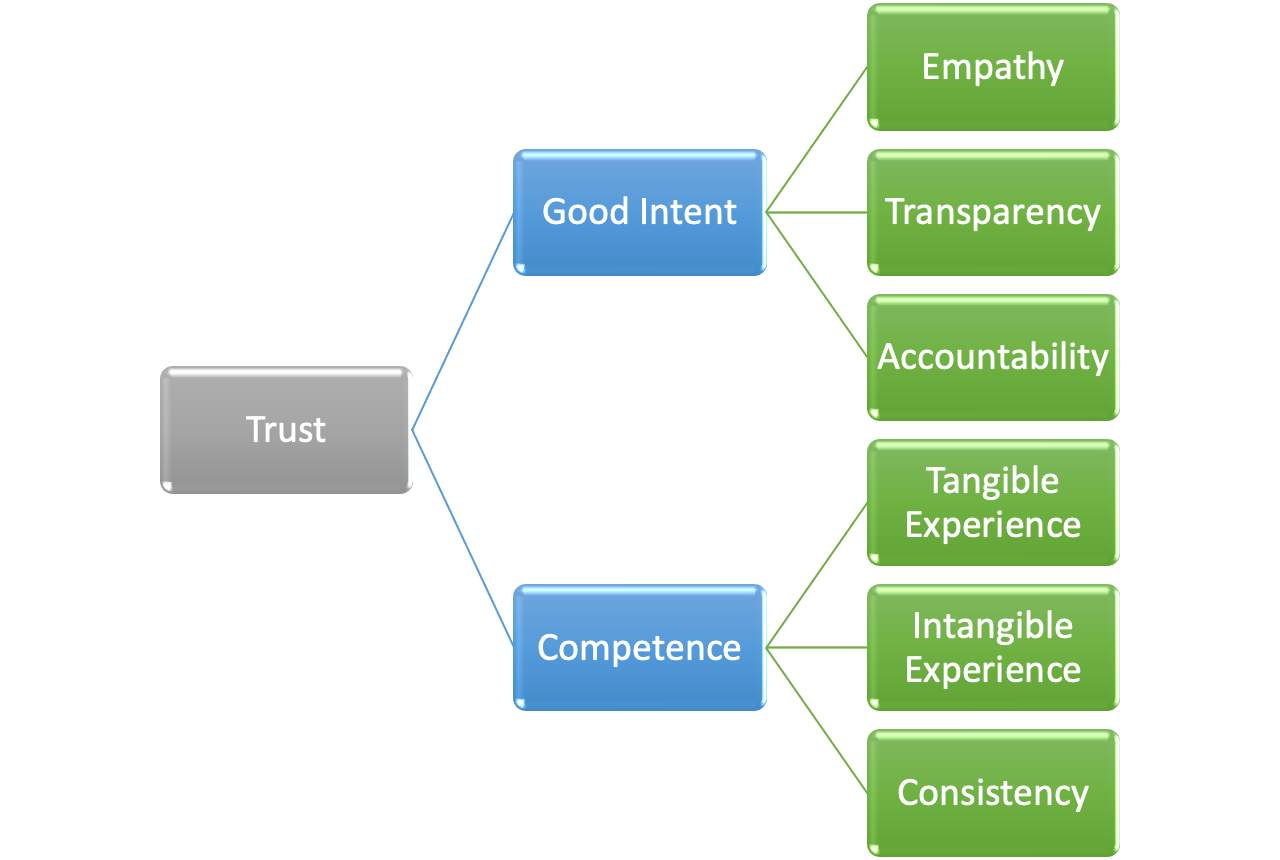

When looking into the concept of trust, I came across a post on ttec.com[1], which discusses the ‘6 Building Blocks of Trust’. The post lays out how trust is built up specifically regarding the relationship between customers and clients, so to consider what makes us trust in the more general sense, I made some adjustments to come up with the following:

As I went deeper into the concept of trust and thought through different examples, this model made increasingly more sense. Firstly, we don’t trust things without them demonstrating good intent. This comes from empathy, transparency, and accountability. Equally, or perhaps more importantly, we need to be able to see evidence of whatever it is we are trusting to be competent. The perception of confidence comes from experience – both tangible and intangible – and consistency.

When thinking about getting on a plane, everything that goes into preparing and checking the plane has the intention of getting to the destination - aligned with your own plans - as do the friendly staff who greet you. If you are flying with a well-established airline you know from the millions of flights that have operated before, safely, that the plane is ‘competent’. It is the combination of these things that makes flying trustworthy.

Good intent starts with empathy - the ability to understand and share the feelings of another. This is vital because knowing that desired outcomes are aligned when putting your faith in something provides certain comfort. Transparency gives you visibility into what the other side is doing, and how they are doing it. It can be helpful to understand that what it is that is being done is aligned with your expectations. Accountability is about taking responsibility when things might go wrong. If things do go wrong but the responsible group or individual is able to put their hands up, apologise and provide genuine assurance that it won’t happen again, you are more likely to believe them.

Good intent is clearly important, but without competence, trust would be difficult. If you had an issue with your health and someone said to you “I want to be a doctor, I can help”, no matter how transparent and how much accountability they are willing to take, you would probably rather go to someone with experience and a track record as a qualified doctor.

All six building blocks are vital, but tangible experience may be the clearest and most evident. How things are done, look and feel are vital for supporting trust. If you get on a plane and the wings are being held on by masking tape, your ability to trust is going to be tested. Intangible experience is also important. Not just what is physically seen, but how you are made to feel. Consistency then helps increase trust over time. Proving results time and time again in a repeatable manner builds confidence. Being able to point to the results you’ve had in the past gives reason to believe it can be achieved again.

The individual blocks in isolation aren’t enough to support trust. 3 or 4 of them working together may be and they are perhaps not completely equal. I believe however that this model helps explain what makes us trust, and why it is more complicated than we perhaps initially consider.

I will never fully understand what it is that keeps a plane in the sky, and I don’t need to. Fortunately for me, we have experts for that, individuals who have dedicated their working lives to ensure what needs to work does. Understanding the inner workings of everything that goes on around us, is impossible and unnecessary.

This is true for countless aspects of our lives, for example healthcare and banking. Trust is not about understanding the working detail or the inner goings on but being able to point to good intent and competence. Once this is proven and accepted, we should be willing to step back and put our faith in others, to fall asleep on that plane, or to take that vaccine. Once it is disproven, communities should be confident and willing to step away or demand change.

A senior member of the British Government speaking in the lead up to Brexit said “this country has had enough of experts”. Whilst not all experts show good intent, this is possibly the saddest statement I have ever heard. Without us thinking about it, or realising, experts make our lives immeasurably easier by significantly reducing the amount that we need to think about. Trust is one of the most important pillars of society, and it is only through good intent, competence, and expertise that we can rely on that remaining the case.

[1] ttps://www.ttec.com/emea/resources/blog/six-building-blocks-customer-trust